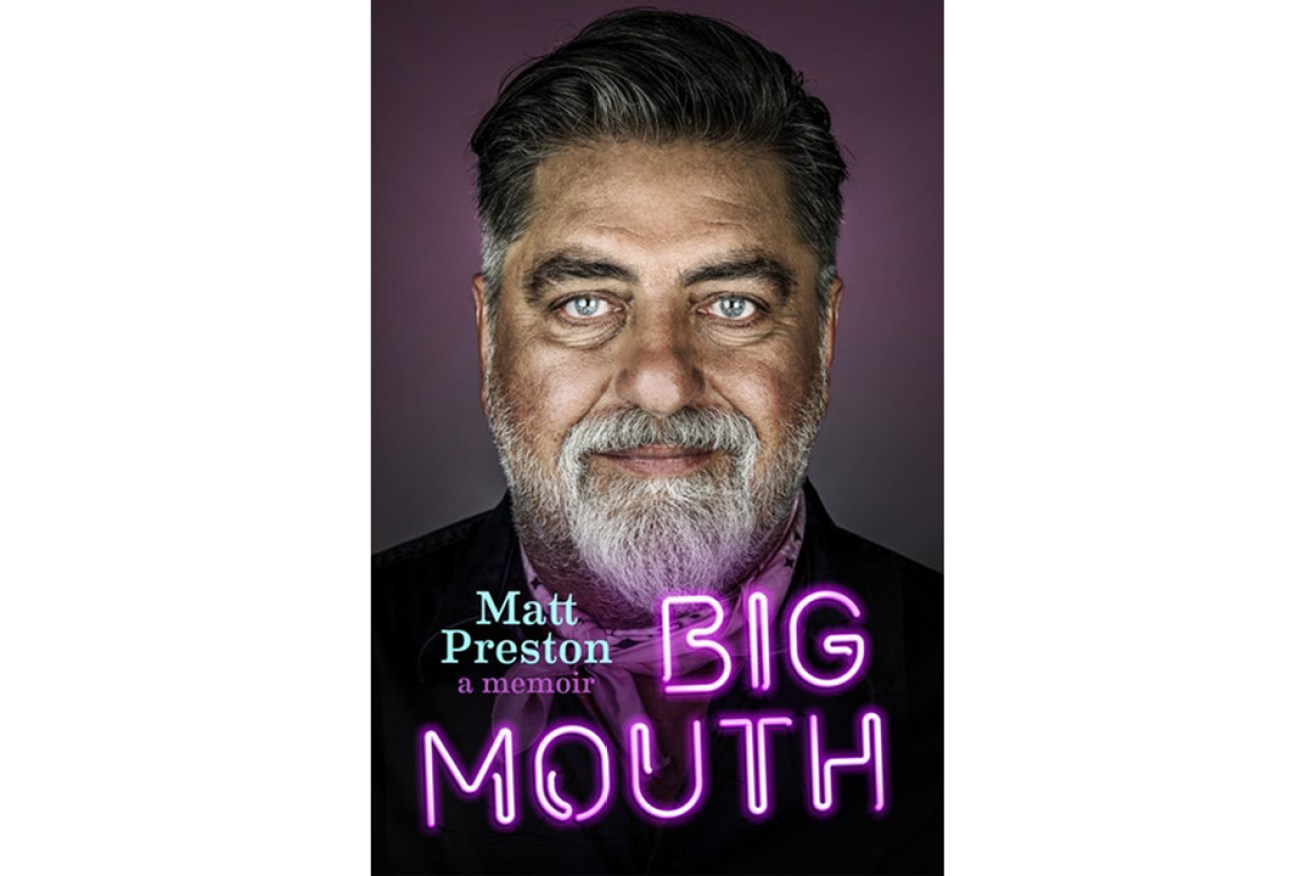

An extract from Matt Preston’s memoir Big Mouth

In today’s summer reading extract, Matt Preston opens up about his early years for the first time – the good, the bad, the tragic and the ecstatic.

When I think of my paternal grandmother, Vivienne, the most vivid picture that comes to mind is of her with a cigarette in one hand and an Americano (vermouth and Campari on ice, with a twist of lemon or a wheel of orange) in a crystal-cut tumbler in the other.

The only child of a fairly loveless, wealthy couple, she was raised by her nanny, someone she spoke of more warmly than her own mother. Vivienne’s father had been wounded at Galli- poli, and mentioned in dispatched landing troops as a member of the British Merchant Marine. He was gutted that his family name would die with his daughter, his only offspring. To compensate, he indulged her, at least as a child.

At boarding school, she was a tearaway. Later she flirted with the new craze, films; Alfred Hitchcock pursued her; and everyone was having fun at parties with nitrous oxide. In her twenties, a romance with a dashing Colombian led to a secre- tive pregnancy and an even more clandestine solution at a clinic in London’s Harley Street. The last thing she remem- bered was the surgeon arriving from dinner in his white tie and tails – silk scarf wrapped around his face for anonymity – to perform the illegal procedure. It was twins, a boy and a girl, she was later told. The abortion was one of her lasting regrets. She cried talking about it.

She fell in love with my grandfather, ‘Boy’, when she saw him working his horse on the parade ground of the old Brighton Barracks. They married towards the end of the 1920s, and as he was with the artillery they were immediately posted abroad – to the one-time pirate haven of Port Royal in Jamaica.

Boy had been born in Rome. His Scottish father was the British Consul in Italy and lived on the Via Condotti. According to my grandmother, Boy’s dad was the ‘biggest bore’ in Rome.

Boy had two older sisters and as the youngest child he was spoilt – the nickname ‘Boy’ came from the fact my grand- mother teased him as being the ‘golden boy’ of the family. His real name was Maurice Rapinet, but everyone called him Boy . . . or the Brigadier.

His severe Scottish exterior concealed the volatile gesticulations and rapid-fire speech that erupted in a flurry whenever he spoke Italian. Teased about his Roman birth during his first week at an uptight English boarding school, that volatility surfaced. He broke the other boy’s nose.

I only ever witnessed his dour Scottish side, but I relished the idea that an Italian-born grandparent meant that I could represent Gli Azzurri, should they one day need me for the World Cup.

My grandparents’ posting to Jamaica was a whirlwind affair. These were the days of nightclubs and balls and sailing to deserted cays for languid picnics. Boy had the rakish movie star looks of a Clark Gable – and he used them. Some nights he’d come in from an innocent smoke on the balcony with not-so-innocent grass stains on the back of his white mess jacket. Furious fights ensued. After one such alterca- tion, Vivienne found herself pregnant. About the same time, Boy was posted to the North-West Frontier (the area between north-west Pakistan and Afghanistan). Here he spent his days gathering intelligence in the markets of what the servicemen called ‘The Grim’. With his skin dyed dark with walnut juice, the Scot with the Italian temperament pretended to be a 6920 Parthan with piercing blue eyes. Back in London, meanwhile, Vivienne gave birth to a son who was christened Michael.

Boy returned from the North-West Frontier with little interest in his new child. To Vivienne’s lasting anger, when he first met him, he described him as ‘quite a bloody little mess’ and seemed more worried about the kid dirtying his dress boots. This was not auspicious. The couple separated at the start of the Second World War. Living on an allowance of £500 a year from her father, Vivienne received permission to stay in the general evacuation zone of East Sussex. The proximity to invasion beaches made property cheap. And it was all she could afford.

While they were there, Michael contracted meningococcal disease and nearly died. Vivienne meanwhile captured a downed German fighter pilot with a sword. She spotted a young downed Luftwaffe pilot floating over the next-door field and was there to meet him as he landed, brandishing her husband’s ceremonial sabre. She could be a frightening woman when roused. She did gain a certain notoriety in the area for marching the German pilot into the local police station in the village at sword point as the local villagers applauded loudly.

There was no love lost down this way for an enemy air force that would jettison bombs on their way home from lighting up London or Coventry, or strafe shoppers on the nearby seafront in Eastbourne. My grandmother would observe when we were there for cream cakes at Bondolfi’s how she’d hugged every inch of the concrete pavement of the beachside promenade as ricochets pinged and fizzed around her.

Like her son, she too fell ill, picking up a nasty type of gingi- vitis known as ‘trench mouth’ – possibly while dating a dashing American pilot from the Flying Tigers. When she found out how much it would cost to ‘civilly’ treat the disease under anaesthetic, she opted instead to have her gums cut away over four painful visits. Although she’d filed for divorce before the war, she told me each time the papers came around she’d send them straight to the bottom of the pile. Her thinking was that if her husband was killed, as a war widow she’d be entitled to his pension. Like I said, no filter.

My grandfather never spoke about his war experiences – but my grandmother certainly did. She told of the hand-to-hand combat with a German officer who was also looking for a forward observation position to direct gunnery for his battal- ion, and how my grandfather was the only one who walked away. There was no time to draw a weapon, so they fought like animals for their survival. It was chilling to realise that the wiry fingers that incessantly tickled me as a small child had fastened round another human’s neck and choked the life out of him.

I never asked him if he had a death wish during the war and after splitting with Vivienne, but he acted with a bravery that suggested that he did. In one European skirmish he was rescuing wounded Canadian troops while their officers appar- ently cowered in their foxholes when he stood on a landmine. It pretty much blew off his arm, but that didn’t stop him – he bent down, grabbed the limb, which was dangling but still attached by sinew, skin and muscle, and carried it back to the field hospital. He argued violently, and with ugly threats, with the surgeon to keep the limb. The surgeon eventually agreed. After a year of rehabilitation and with his arm reattached and fully functioning, he was offered a desk job but preferred to take a demotion and a cut in pay to return to the action with a command in the field, now fighting the Japanese in South-East Asia. He arrived there with another medal, the DSO, on his chest for the men he’d saved on the fateful day.

At the end of the war, as a colonel, he had to accept the surrender of a Japanese regiment. The process was simple; the Japanese officers would walk up to him and hand over their swords. Many of these weapons were family heirlooms of great antiquity and artistic value. However, one man was so distraught that my grandfather took pity on him and gave him back his sword. It was the wrong thing to do. The soldier took it as a mortal insult and committed impromptu seppuku there and then, ruining, my grandfather said, another perfectly good pair of boots. Not much love lost there either.

After the war my grandparents reunited – one of the first couples in the UK to file for divorce and then subsequently remarry – and were transferred to Germany, where my grand- father oversaw a region of the conquered country, replacing the deposed gauleiter. Shocked upon visiting one of the concentra- tion camps and witnessing first-hand the horrors that had taken place, my grandfather hired cinemas in the area and compiled a list of all the local German survivors. Each was checked off once they had watched gruelling newsreels of the liberation of the camps so there could be no denial at a later date of the atrocities committed. On a lighter note, I still have a beautiful painted Bavarian bread-proving cupboard my grandmother bought for 5 deutsche marks.

Boy returned to the UK as a decorated brigadier and went on to do something shadowy with a right-wing organisation known as the Economic League. If you’ve seen the TV series Peaky Blinders, you’ll know the sort of things they got up to. I remember there was a big chart on the wall of his London office that featured known communists and trade union activ- ists – and their whereabouts. As a child I would wait quietly studying this blacklist before we’d cross the road to Victoria Station and the trip down to the thankfully agitator-free East Sussex.

Here he was the perfect doting husband and the best grand- father a lad could hope for. The anger and offhand nature had deserted him. He made a breakfast tray for my grandmother every day, and provided the sweat and muscle that enabled her to pursue her lifelong love of gardening. The lush, lined lawns and herbaceous borders packed with height and colour were in large part down to him. I’d follow him around the garden asking endless ques- tions. Whenever I disappeared for too long he’d sing out, ‘Mr Chatterbox, where are you?’ and I’d come running.

We’d go for long walks over the Downs no matter the weather, and careen down the slopes of the garden in fertiliser bags or on kitchen trays when it snowed. He taught me skills that I still use today, like how to split a log with a sledge- hammer and wedges, how to chip for kindling and how to swing a lawnmower down a steep, grassed slope with a rope. In many ways, he was the father to me that I’m not sure he ever was to his own son.

This is an edited extract from Big Mouth by Matt Preston, out now.