Vaccinations tipped to be shot in the arm for beef growers

If COVID-19 vaccines give people confidence to dine out again, that would help producers of premium Queensland grain-fed steaks.

Cattle on feed at Kerwee Feedlot, near Jondaryan on the Darling Downs. (Photo: Supplied).

China’s suspensions of some Australian beef imports last year resulted in the biggest contraction in total Australian beef volumes to that country on record, but demand from Japan for grain-fed beef remains relatively stable.

According to figures from Meat & Livestock Australia, Japan accounted for 45 per cent of Australian grain-fed beef exports in 2020, making it the category’s largest and most reliable export customer.

Analysts say a resurgence in restaurant dining promises to improve those figures further in 2021 by returning life to the lacklustre food-service channel, which took a major hit globally when consumers were forced to eat more at home.

Despite trade tensions and the pandemic’s continuing legacies, the world is still hungry for affordable, safe, and nutritious beef.

That’s the view of Bryce Camm, the president of the Australian Lot Feeders’ Association (ALFA), which turned 50 at the end of last year.

“It’s a genuine Australian success story, which started in Queensland and continues to drive improvements by being innovative and adaptive to change,” Camm said.

“Our history was forged by being at the forefront of what’s acceptable to the consumer, the community and the regulator and I see our future being no different.”

For the 2000 people directly employed by the industry and the thousands of producers who supply cattle into the system of some 450 accredited feedlots across the country – 60 per cent in Queensland – they had better hope Camm is right.

Growing demand, Camm says, means a continuing place for the grain-fed sector, which plays a critical link in the beef supply chain to finish cattle at a premium standard with the risks of variable seasons, lack of water and deficient pastures removed the equation or at least reduced.

As good as Australia’s cattle producers are, natural pastures at the mercy of the weather would be unable to produce beef volumes at a consistent quality, flavour and tenderness that Australian meat-eaters have come to expect without the support of grain finishing.

Grass finishers, producers who start and end their livestock’s life cycle purely on grass without grain supplementation, produce a quality, in-demand product, but throughput will be dictated by Australia’s increasingly capricious climate.

But all that grain assisted polish on the final product comes at a cost. Along with the live export of cattle, there is probably no other segment of the livestock business that attracts the glare of public scrutiny more than lot-feeding.

Challenges ahead

Lot feeding’s social licence to operate headwinds are myriad – and they’ve been swirling for years and gathering strength.

In no particular order, there’s animal welfare: are large animals meant to exist in such close quarters eating nutrient-dense rations of grain for an average of 90-120 days, susceptible to infections such as bovine respiratory disease and heat-stress during long summers?

For the high-end Wagyu and British-breed types such as Angus and Hereford that eventually end up as premium grilling cuts in five-star restaurants, the feeding program can take as long as 500 days.

Then there’s the environmental footprint: methane emissions from belching cows, effluent and odour management, water security, energy utilised to grow and supply the grain, and the livestock trucks on roads to cart the animals from paddock to feedlot and then to processor, the last on that not-exhaustive list, also raising animal welfare concerns.

Beyond the technical and structural challenges that the industry manages, there are also shifting changes in consumer sentiment and behaviour that’s a headache for marketers of beef in general – but particularly if it’s grain-fed.

At one end is the militant vegan, swearing off meat altogether and vigorously advocating for others to do the same, to those who believe meat consumption should at least be tempered on environmental, animal welfare and human health grounds.

And if humans feel the need to eat meat, then it should only be from animals who spend peaceful lives eating plentiful natural grass in open grazing country, just as nature intended.

It’s another argument among many, at the opposite end of an increasingly crowded and convoluted anti-meat spectrum.

And let’s also not forget the growing presence of plant-based ‘meat’ and the nascent development of synthetically-grown meat still being refined in test-tubes and petri dishes, but with its day in the sun surely to come on retail’s not-too-distant horizon.

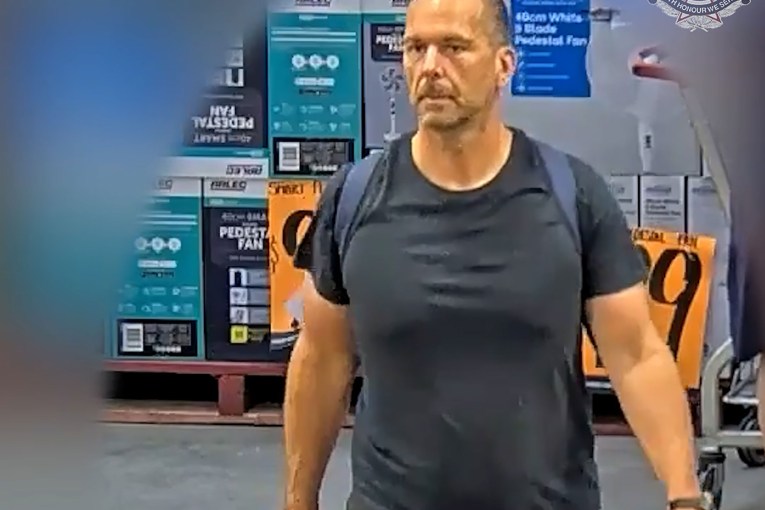

ALFA president Bryce Camm.

Industry vision

Camm, whose family operates a large feedlot near Dalby, among other large beef holdings throughout Queensland, has been ALFA president since 2018 and a councillor since 2011.

He is also the chair of Beef Australia, the country’s largest beef exposition that’s been held every three years in Rockhampton since 1988. Assuming Covid is kept at bay, the event is planned to go ahead in May this year.

For the moment, Camm is arguably Australia’s chief beef ambassador and salesman, and he’s proud to acknowledge the role grain-fed beef has played in creating a more profitable, sustainable and sophisticated beef industry, while providing consumers with a more consistent, higher quality product at a more affordable price.

He told InQueensland that was the vision that saw the industry galvanise from what began as a few independent producers tinkering with lot feeding in the late 1950s to the formation of the Queensland Lot Feeders Association that grew into a national body, formally established in the Wambo Shire Council building in Dalby on December 18, 1970.

As noted in the book Grain Fed: the history of the Australian cattle lot-feeding industry by Jon Condon and Bob Coombs:

“With little fanfare or sense of occasion, ALFA was born on that day in a room with 11 people present, a low-key event which nevertheless stands as a significant landmark in the history of the Australian beef industry.”

Some of the organisation’s major achievements include being a key driver of Australia’s world-leading Meat Standards Australia (MSA) program, a testing regimen to align beef cuts with consumers’ expectations that helps to ensure consistency in cooking performance and the eating experience.

Supermarket giant Woolworths, for example, uses the MSA graded beef logo on its meat packaging, both as a promotional tool and point of difference to its competitors.

ALFA operates under Australia’s oldest agriculturally based quality assurance program, the National Feedlot Accreditation Scheme (NFAS) which turned 25 last year.

The organisation also works with the RSPCA on animal welfare guidelines and has a program in place to have all feedlots shaded within six years to further safeguard animals from heat stress-related health problems.

“The beef supply chain is inextricably linked and we work collaboratively across all links of the chain to continuously improve environmental and animal welfare outcomes,” he said.

“The reality is the modern grain-fed production model is not only playing a more critical role for brand owners and the meat supply chain, but for beef producers generally, because it provides options, especially when seasons are tough.

“This means that when drought bites hard we don’t see mass destruction of cattle or widespread denigration of natural grazing land.

“We have feedlots who can take that cattle and bring them to market safely and in good condition.”

2019 was a case in point, with cattle on feed reaching a record 1.24 million head for the December quarter, comprising the more than 3 million head that are fed in feedlots in an average year.

This was on the back of drought, admittedly, when producers look to offload cattle from moisture-stressed paddocks, but the industry itself grew capacity by more than 60 per cent between 2000 and 2017 attributed to consumer demand here and overseas.

According to Deloitte, if lot feeding were to disappear, $10.3 billion would shrink from the Australian economy and 49,000 full-time jobs would be lost, hitting women especially hard who make up a third of its workforce.

ALFA celebrated its half-century prior to Christmas with a series of events at feedlots linked via video prior, which also included the announcement of the Young Lot Feeder of the Year, with Molly Sage, from the JBS owned Beef City feedlot near Toowoomba, winning the title against finalists from Victoria and South Australia.

Disclosure: The author of this article is a former editor of Lotfeeding Journal, ALFA’s official industry publication.