Spotlight on our born-again rural maternity vision

An international day to recognise premature babies has put the spotlight on Queensland’s lead role in reviving rural maternity units.

The outcomes of premature birth can be traumatic and have life-long implications. (ABC photo)

National Rural Health Commissioner Professor Ruth Stewart has applauded the Palaszczuk Government’s efforts to restore rural birthing, urging other state governments to follow the Queensland lead.

The highly credentialled doctor and health administrator was speaking at the National Rural Press Club in Canberra honouring World Prematurity Day in recognition of preterm births and their complications.

A GP and obstetrician by training, who spent decades working in rural Victoria before relocating to Thursday Island, Stewart is confident premature births can be halved if mothers are kept closer to their communities and have access to continuity of care.

“In fact, remote women are nearly twice as likely to give birth prematurely. In 2018, 8.4 per cent of births in major cities were premature compared with 13.5 per cent in rural, remote and very remote Australia,” she said.

“Those averaged figures hide pockets of greater complexity. In east Arnhem Land communities, 22 per cent of babies are born prematurely.”

Stewart’s assessment of Australia’s rural maternity care performance comes after the publication last year of a report from the Rural Maternity Taskforce, chaired by Queensland Health director-general Dr John Wakefield.

The report highlighted 1996-2005 as the peak of the rural maternity crisis, when 130 birthing units folded across rural Australia.

As reported previously by InQueensland, the rapid closure of rural birthing units accelerated in a near perfect storm of outdated workforce planning, outmoded training and the collapse of insurer HIH which sent premiums for obstetric indemnity skyrocketing, a final gust of ill-wind that sent an already fragile network to the wall.

“The closure of maternity services has not been a slow, steady progression over a few decades as suggested by the media,” Wakefield wrote in his report.

“While a number of services closed between 1996 and 2005, service numbers have remained relatively stable since then. From 2011 to 2017 six services closed and five opened.”

Services that have reopened include Beaudesert and Cooktown under former LNP health minister Lawrence Springborg and Ingham earlier this year with outgoing health minister Steven Miles at the helm.

A further four rural locations are now being considered for new maternity units by incoming Health Minister Yvette D’Ath at the recommendation of the taskforce – Cloncurry, Bowen, Theodore and Weipa, the latter particularly significant as it will allow Indigenous women to birth on-country.

Good health starts at birth

It’s almost universally accepted in medical circles that producing healthier outcomes for people, especially in rural settings, starts at the beginning of the human life cycle, literally access to well-equipped and well-resourced birthing units.

Once those facilities are downgraded or closed, other clinical services such as surgery and chronic disease management will follow suit.

As Stewart outlined to her audience today, one of the justifications for closing rural maternity services is that there are economies of scale in concentrating birthing services in large centres.

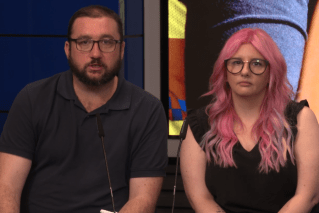

National Rural Health Commissioner Professor Ruth Stewart, pictured on the Gold Coast last year.

“I would agree with that, but I would suggest that this is a cost and risk-shifting exercise,” Stewart said.

“Rural and remote women, their families and their communities carry a burden of cost and risk when a pregnant mother transfers to the larger centre a month before her birth is due, or drives perhaps hundreds of kilometres when in labour.

“Those costs are counted in financial, social, cultural and emotional terms and can seriously destabilise vulnerable women’s and babies’ lives.”

Stewart’s observation has big implications for Queensland where a greater proportion of people still live outside their capital city than anywhere else in Australia.

Of the 40 public maternity facilities that currently provide birthing services in Queensland, 32 are located in regional, remote and very remote areas.

The majority of these services are at a level which can provide planned births for a healthy woman with a pregnancy of 37 weeks’ gestation or greater and who is expected to have a trouble-free labour.

The data crunched by the Rural Maternity Taskforce found that about 96 per cent of women who give birth live within a one-hour drive of a public maternity service.

Of the remaining 4 per cent who live an hour or more from that service, a third are Indigenous.

For women living four or more hours from a maternity service this increases to 80 per cent who are Indigenous.

Perinatal and neonatal mortality rates were a maximum of 1.7 times higher for women in very remote areas compared to women in regional areas.

As the taskforce suggests, the loss of rural birthing services more than two decades ago has established a culture within some clinical and administrative cohorts to centralise maternity services within major towns and cities.

This approach could be generating unintended, but still adverse consequences, such as draining skills and resources from rural hospitals and contributing to more women opting for home births or emergency birthing on the roadside due to the long distance they have to travel.

“This increased rate was found to be partly explained by maternal health factors that can be modified by good access to social and health support before and during pregnancy,” the report concluded.

“The main conclusion from this is that more work needs to be done to support better general health of women in rural and remote areas, including improved access to primary and preventive health services and better social care services.”

Thursday Island lessons

Stewart’s message to Australian health practitioners and planners is to follow Queensland’s lead and fast-track the training and recruitment of more generalist doctors into rural areas – those with a wide scope of practice such as GP skills, minor surgery and obstetrics rather than doctors with narrow specialisation.

“In the Torres Strait where I live on Thursday Island, the introduction of a midwifery group practice supported by Indigenous health practitioners and rural generalists – that is GPs with obstetric skills and GPs with anaesthetic skills – has seen a halving of premature birth rates, a significant reduction in the percentage of mothers who smoke at any time in the pregnancy and a reduction in the percentage of low birth weight babies born,” she told guests in Canberra.

“This past year none of the 300 or so babies born were classified as low birth weight. This is a service where all pregnant women are welcomed.

“So, it is not simply the outcomes for women who were destined to travel smoothly through pregnancy and childbirth. Some of these women were considered to be at high risk of having a poor outcome.

“This model was co-designed with the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities and cultural safety and empowerment are front and centre. We think that this is what makes the difference.”

Stewart is confident the outcomes on Thursday Island can be applied to all women expecting babies regardless of where they live.

“We now have good evidence that midwifery group practice and continuity care models can reduce the incidence of premature births in urban and in remote Indigenous communities,” she said.

“We just need to increase rural women’s access to maternity services with such models of care.

“That’s what we need to do, but the sad truth is that for rural and remote Australian women access to the maternity care they want, need and deserve has been decreasing for decades.”

With two new deputy rural health commissioners to be announced soon, one of them a designated Indigenous health professional, Stewart has committed to increasing the number of rural generalist doctors, nurses and allied health professionals across rural and remote Australia – a model that had its genesis in Queensland.

“I will be working with each state and territory government to develop the workforce that is needed for strong multidisciplinary primary health care teams to turn around the health of the nation,” she said.

“I call on all governments in Australia to stop the closure of rural maternity services and to follow the lead of the Queensland Government in re-establishing birthing in rural and remote communities.

“Now is the time to halve the rural rates of premature birth and improve the health status of rural and remote Australians.”