Special report: The Queensland script to cure rural pain

Last week’s announcement in Canberra to fund an extra 100 places for rural medico trainees may be just what the doctor ordered for people living in rural Australia thanks to some Queensland country ingenuity and “can-do”.

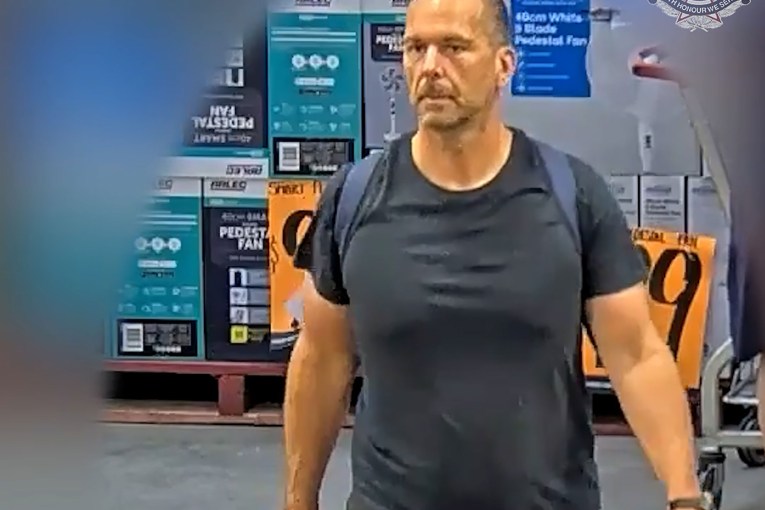

Emergency medicine training director Dr Julia De Boos at the Mount Isa Hospital. Photo: (supplied by Northern Queensland Regional Training Hubs)

There was a time when the healthcare needs of rural, remote and regional Queenslanders – more than half the state’s population – was held captive by a mindset better suited to running big city hospitals and medical clinics in the suburbs.

Rural health advocates who have been fighting to change that thinking for decades may well argue the battle is far from over, although there’s no doubting they won massive ground last week when Rural Health Minister Mark Coulton announced funding for an extra 100 training places via specialist provider the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine (ACRRM, pronounced ac-rim).

While rural Australians will welcome those extra boots on the ground when they arrive, the more significant shift contained within this development is the now-confirmed view that rural people have unique health challenges that can only be adequately treated by doctors in their local communities with broad skills and a recognised wide scope of practice.

And so, the “rural generalist” now enters the medical lexicon as a specialty career path for medical graduates within the specialist sphere of general practice.

But like most overnight success stories, the concept of the rural generalist is nothing new. In fact, it goes back more than three decades, when the city-centric, cookie-cutter medical model producing often sub-standard outcomes for rural doctors and their patients alike, gave birth to a groundswell rural doctors movement, starting in NSW but then accelerating with the incorporation of the Rural Doctors Association of Queensland (RDAQ) in Roma in 1989.

Model of a modern major generalist

RDAQ’s founding president, Dr Col Owen, who still practices in the southern Darling Downs community of Inglewood, is the model of the rural generalist.

You know the type – that salt of the earth character who can deliver a baby in the middle of the night, patch you up after slicing a digit on some piece of farm equipment or whipping out your appendix when a surgical team is just too far away to safely treat the emergency in time.

Anyone who has ever had the misfortune of breaking down in their car on a lonely rural road, will know the relief when a friendly local gives their vehicle a tow into town where the mechanic has the confidence to give it the once-over, get it sorted and back on the road, without putting it on a truck and sending it to a large regional centre for specialist treatment. No fuss, no hassles, no worries.

That’s what patients want from their rural doctors – smart, well-trained professionals who understand their needs and bring to their scope of practice a dash of country “can-do”.

It would seem like a logical solution, especially in a state the size of Queensland with the nation’s most decentralised population.

But even in the first decade of this century, rural health care in Queensland, not to mention the rest of the country, was still in a mess.

The Longreach experience

Dr Clare Walker, the current RDAQ president based in Longreach, tells the story of her husband David, also a doctor, who completed his 12-month internship at the Royal Brisbane Hospital and was then flown to Babinda, 1600km away in north Queensland, to look after one hospital and one clinic on his own for six weeks straight with no relief for a catchment of nearly 4000 people.

Just let that sink in. He was only 24 and this is just one example among hundreds.

“We used to see this kind of thing all the time, a lot of junior doctors rostered on in rural hospitals. It was something of a rite of passage,” Clare Walker says.

“It seems to have been phased out now but it was common practice to send mostly city kids with only big city hospital experience into small rural communities as rostered relief with ‘take care, hope everything goes well for you’ as their only support.”

Dr Clare Walker

If the experience for new graduates and trainee doctors was stressful, it wasn’t much better for more seasoned doctors practicing in rural locations.

“In the bad old days, and I’m only talking less than 20 years ago, a town might have had only one, maybe two doctors. Those doctors were invariably male, they worked 80 to 100 hours a week, and their miserable spouse stayed at home and looked after children that they never saw because they were always on-call, lurching from one medical crisis to the next because they never had the time to devote to preventative care,” Walker explains.

“So what the patient experienced was a doctor who was fatigued, stressed due to competing priorities and stretched, which often meant extremely long waiting times.

“On top of that, rural doctors weren’t paid well in comparison to their city colleagues, so it wasn’t a very attractive career option, which only exacerbated the doctor shortage and eroded the level of care.

“Then in the early 2000s we had the indemnity crisis, when insurance premiums for specialised services such as obstetrics went through the roof, forcing doctors to abandon birthing, which then saw maternity units closed, leading to a further downgrading of other medical services available.”

The Walkers’ journey to Longreach also demonstrates the depth of the state’s medical malaise at the time. When they took up residence in the western Queensland town in 2010, it had been 20 years since the community had benefited from a permanent family general practice.

Local medical services had effectively been propped up by two willing doctors and a steady stream of rotating overseas trained clinicians.

Clare Walker, who grew up on a dairy farm at Harrisville in southeast Queensland, had a yearning to be a rural doctor. David Walker’s mother, Carmel, had worked for many years in Cape York and later Cooroy in the Sunshine Coast hinterland.

They both had a natural affinity for rural life but had to follow their own pathway before a rural generalist framework was conceived, taking them to such places as Atherton Hospital, Ravenshoe and Cairns to ply their craft and gain accredited skills suitable for a rural doctor.

They settled on Longreach because they genuinely liked the community and they saw the obvious need for a stable medical service.

“Longreach is also far enough away that medical services from here could never be feasibly contracted and centralised to a city or large regional centre,” Clare Walker says. “The tyranny of distance would just prevent that from happening, so it was also a business decision.”

Part 2 of Bush medicine continues tomorrow: In a class of their own – building the rural doctor