Money makes the world go round, so why did we fall so out of love with economics?

Three and a half decades since Paul Keating introduced us to Banana Republics and recessions we had to have, the shine has gone off economics, writes Shane Rodgers.

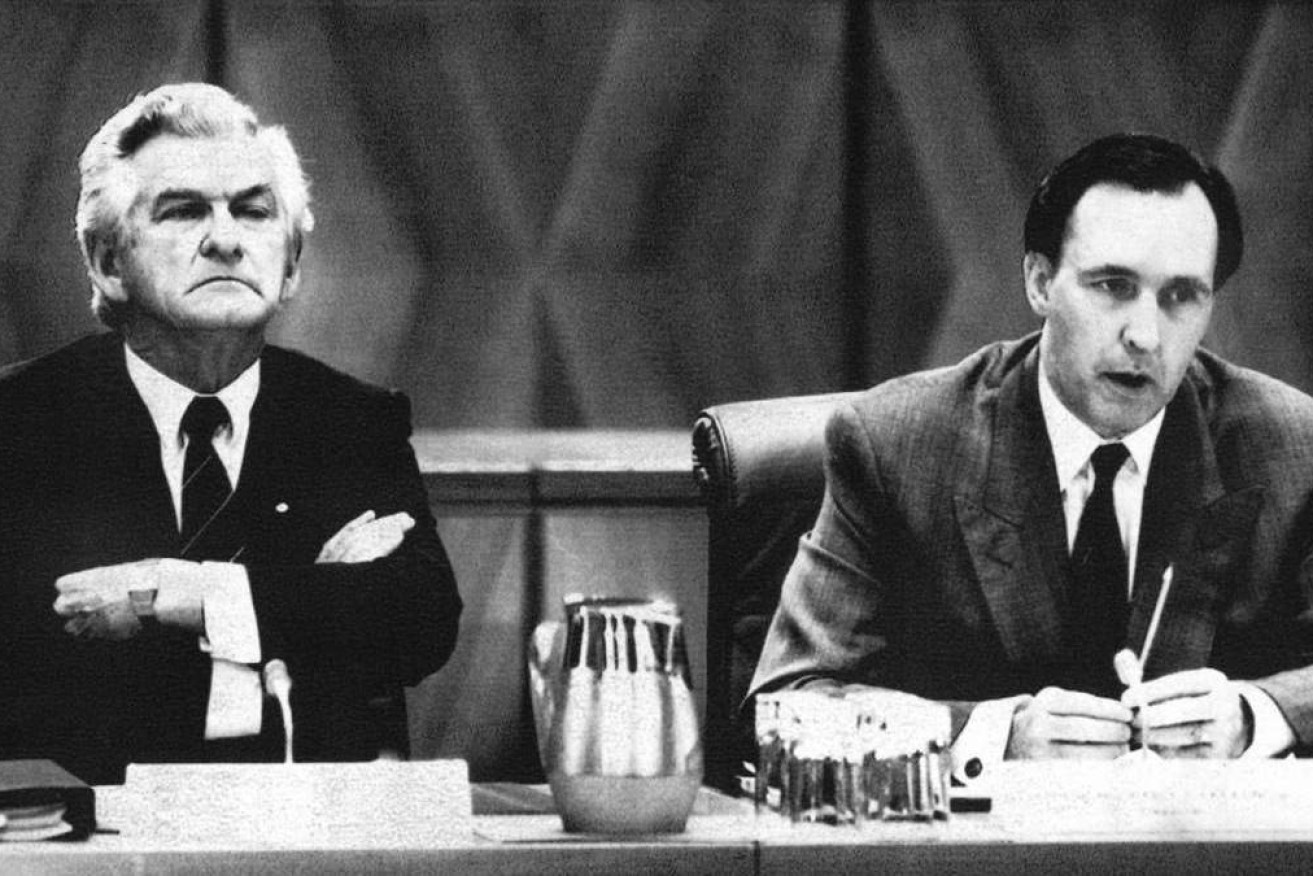

Paul Keating, pictured with ex-PM Bob Hawke during the 1991 Premiers conference was always ready to give the nation a lesson on Banana Republics and recession we had to have. (Photo: Peter Morris)

Back in the 1980s the then Treasurer Paul Keating took pride in declaring that he was Australia’s economics teacher, driving major reform backed by solid lessons on why it was necessary.

Sometimes his lessons were memorable. In 1986 he declared that we were on track to become a “banana republic” if we did not address a growing trade deficit. In 1990 he declared two quarters of negative economic growth was “the recession we had to have”.

As a 22-year-old economics and industrial relations reporter in the Canberra Press Gallery, I always looked forward to the economics lessons, even the ones delivered loudly in the morning after Keating read the papers and decided we all got our homework wrong.

Looking back, the 1980s and 1990s were a golden era of economics. It seemed a vital component of our national conversation and the economics data represented a compelling narrative on the shifting sands of Australia’s fortunes.

But how things have changed.

A study by the Reserve Bank of Australia a couple of years ago revealed a 70 per cent fall in the number of Year 12 students studying economics between the mid-1990s and 2019. In number terms that is a drop from about 40,000 students to about 12,000.

Economics went from the third most popular subject in Australian high schools in the 1990s to the curriculum wasteland at a frightening pace. A recent report by Professor Gigi Foster of the University of NSW School of Economics said that economics was now taught at less than one third of government schools and about half of non-government schools.

As someone who has always loved economics and put it on the top of my subject choices, I find the trend particularly unnerving.

I was first alerted to the sad decline of the discipline when my youngest daughter told me some years ago that it was not on the subject list at her school. I thought this must have been a mistake. But, sure enough, it was dropped due to poor utilisation combined with a shortage of teachers. My daughter ended up having to do it externally.

According to the various Reserve Bank surveys over recent years, economics has an “image problem”.

“The Bank’s liaison has found that too few students understand what economics is and how it might be relevant to them,” the RBA report said.

“Too few educators are equipped to teach it, and a growing share of high school teachers are delivering economics courses without having studied the subject. Too few career advisors, or educators at large, can articulate how economics is used in the workplace. And too little relevant Australian economic content and teaching resources are available.”

There is also a theory that a long period of relative prosperity for Australia took the edge off interest in economics.

Looking back to high school, my interest in economics was piqued when the teacher said it was effectively the study of human behaviour. Too often it is seen as boring numbers and mathematical modelling.

In reality, it is a science that goes to the heart of how humans interact to allocate scarce resources. So much of economics has its core in how people feel when they get out of bed in the morning. It is vital that we understand this.

Much of the action that economics once enjoyed in school has now been taken over by business studies. These are important, but they are not a direct substitute. Particularly now.

At a time when social and environmental reform is charging up the political agenda, we will need a high level of knowledge about the nature of wealth creation (and subsequently job creation) and the delicate balance that will be needed to create a more sustainable world without massive economic and social fall-out.

We cannot fix all of the world’s problems unless there is an economic model underpinning the solutions program that actually works and can be funded.

There is something a little perplexing about going into the next era of fundamental technological, environmental, workplace, industrial relations and social reform without a rising sea of young economists to model, question and find new approaches to fresh challenges.

It also worries me that the new waves of young voters are making big decisions on our economic direction without a solid grounding in how economies work.

Perhaps we need to ask Paul Keating to dust off his economics textbooks and start the lessons again. Thirty-six years later, we still don’t want to be a banana republic.

Shane Rodgers is a business executive, writer, strategist and marketer with a deep interest in what makes people tick and the drivers of change. Comments in this article are personal and not related to his day job.