Surely our darkest crisis is not the time for politicians to be keeping their distance

By cancelling the next scheduled sitting of Parliament without a plan B in place, the Morrison Government has failed a COVID-19 test that parliaments elsewhere around the world have managed to pass, writes Dennis Atkins

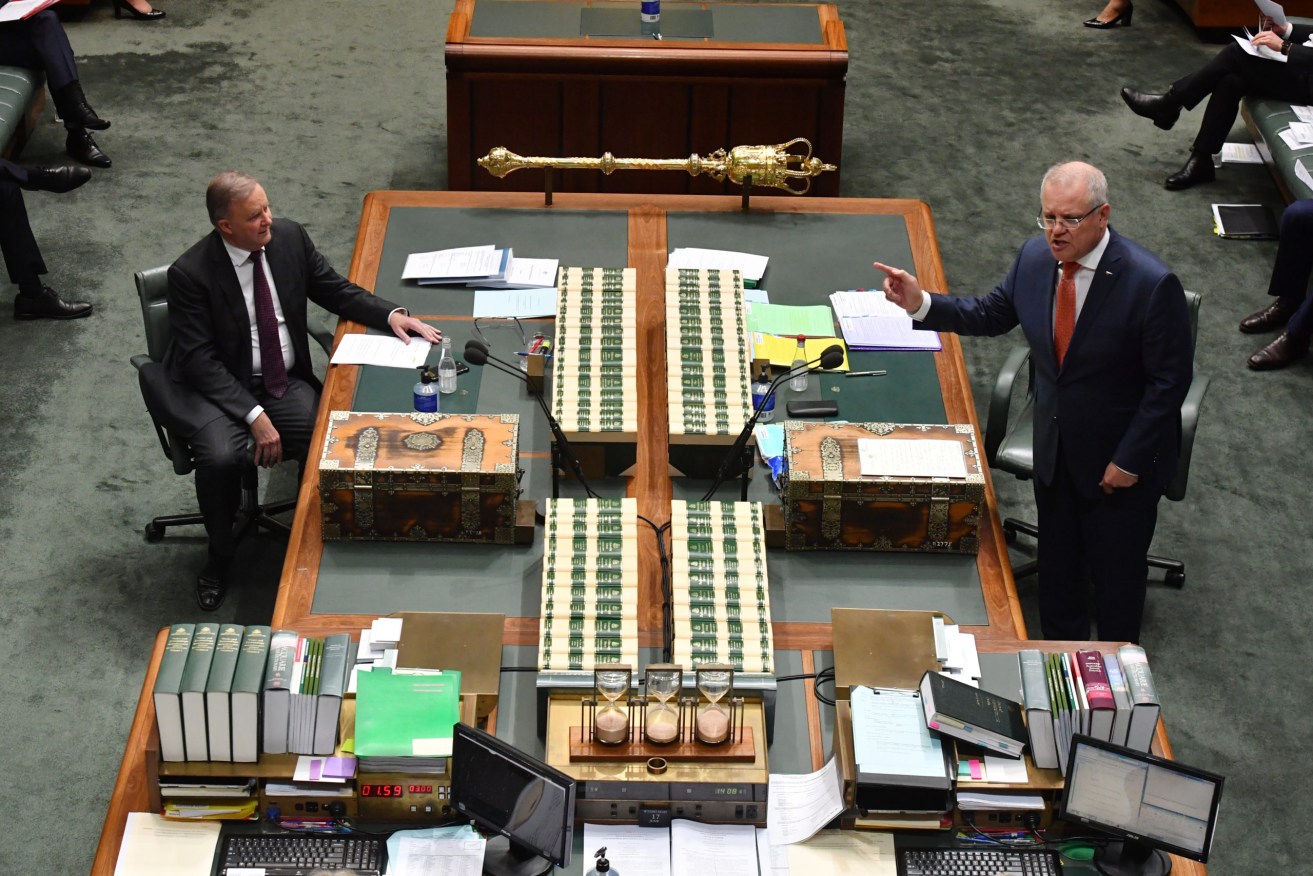

Leader of the Opposition Anthony Albanese and Prime Minister Scott Morrison during Question Time in the House of Representatives.. (AAP Image/Mick Tsikas)

Parliaments around the globe are managing to live in a COVID-19 world, with most continuing to meet either with pared-back numbers or having hybrid in-person and remote attendance by politicians under reimagined standing orders.

Even though we are now at almost six months of living with the full health and economic – public and private – consequences of the pandemic, the Australian Parliament has come up against its first significant challenge and failed.

With a still unfolding public health emergency in Victoria and one barely in check in New South Wales, Commonwealth chief health advisers, the Government and the presiding officers in the Senate and House of Representatives have decided to take the easy way out when considering the proposed two weeks of sittings due to begin on August 4.

It’s not as though this problem hasn’t been anticipated. In March, Christian Porter, the Government Leader of the House, made allowance for the extraordinary circumstances then still unknown by changing basic rules so that the House could “meet in a manner and form not otherwise provided in the standing orders”.

Since then minor changes have been made – the number of MPs and senators needed in Canberra has been cut with agreement on extended pairing arrangements, physical distancing has been practised and some MPs have been joining in remotely.

The parliament’s committee system has been operating with teleconferencing being used for members and witnesses around the country.

Parliaments around the world have adopted various new ways of doing things. Almost none has shut down during the pandemic with some, such as the United States House of Representatives and Senate, making no changes to the way they do things.

The British Parliament, from which Australia often takes a lead, has a hybrid system in place. This model allows questions and statements to be delivered both in-person and via video conferencing platforms.

The House of Commons has been fitted with screens and can sit 50 members in-person and have 120 members online. Proceedings in these circumstances are organised by the speaker and government two days in advance.

The Government did need to heed the advice of Acting Chief Medical Officer Paul Kelly, who said at the weekend it was dangerous to have “a large number of people from all over Australia converging in one place for an intense period and then going back to their normal places”.

It would be “deemed a mass gathering and we would feel that there is a high risk”.

However, the Government could have taken this advice, said it would be considered over the coming week or so and alternative arrangements would be examined.

Suggestions that Victorian MPs would not be allowed to come to Canberra for normal parliamentary business should not be taken as the final word, despite Prime Minister Scott Morrison saying it would be neither “feasible nor desirable” to exclude politicians from one state.

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg, a Victorian MP, has been given a special dispensation to travel to Canberra this week with particular strictures on his movements.

Similar Victoria-specific rules could be drawn up for MPs from that state, backed with rigorous testing prior to leaving home, on arrival in Canberra and during the time they are there.

These things should not be beyond health and parliamentary officials – especially if the number of politicians from Victoria is kept to the absolute minimum.

Many would agree with University of NSW adjunct professor and strategic health policy advisor Bill Bowtell who deemed it “unacceptable” the Government didn’t have a plan B in place.

“Are we really saying it’s beyond the capacity of Parliament to sort out a Zoom meeting like everyone else? Seems odd to me,” Bowtell said.

“The Chief Medical Officer has somehow found the situation with COVID-19 was so extraordinary it had to abandon its sitting. That’s not living with COVID. That’s giving in to it.

“Every other parliament in every other country has gone on.”

Anne Toomey, professor of constitutional law at Sydney University, said Parliament must continue to meet one way or another.

“In an emergency, maintaining public confidence in government is essential,” Toomey said. “One way of supporting this is to ensure parliament can operate, to scrutinise government action and represent the wishes of the people.

“If the physical presence of MPs is not possible due to a pandemic, there is good reason to ensure such scrutiny and representation can occur by electronic means.”

At the moment the National Government has failed this test. They’ve got two weeks to find a way of fulfilling their obligations.