Beyond battlefields, why Ukraine is winning the food security war

Twelve months since the invasion, the resolute defence of Ukraine against Russian aggression is being matched by the country’s renowned grain growers, who are protecting against their food security threats far better than their belligerent neighbour.

The view from respected grains market analyst Dennis Voznesenski is that Russia’s enormous grains complex, where massive corporate farms of more than 200,000 hectares are not unusual, could be vulnerable to major shocks if the invader’s campaign continues to falter and bleed money.

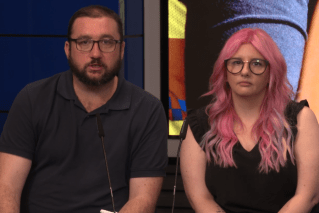

The Sydney-based grains analyst for Rabobank, who is a frequent visitor to Queensland, shares a heritage with both countries, with grandparents from Russia and Ukraine.

Born in Australia after his parents fled the collapsing Soviet Union in the early 90s, Voznesenski was touring grain operations on the Darling Downs recently, where growers on the southern grains belt and others across the state have joined their colleagues from across the nation in producing one of the biggest crops on record, according to estimates.

With the Downs’ black soil still caked on his boots, Voznesenski called into the InQueensland newsroom in Brisbane to provide his assessment on overseas developments before flying back to the NSW capital.

While Ukraine’s military defence rightly gains the attention, Voznesenski says he has been astounded by the country’s ability to not only maintain some level of production, but upgrade its logistics infrastructure to ensure it still has a channel to market.

“In Ukraine they will be harvesting in July and August and this will be the first large winter crop planting harvested since the war began,” he said.

“It is estimated the harvest could be down as high as 45 per cent, which is understandable given it is now a war-torn country with some parts not even in Ukraine hands.

“But where it gets interesting is that exports, in terms of what Ukraine is moving out of the country not only by sea but via road and rail, are fairly similar to what they were before the war.”

That’s because, as Voznesenski explains, engineers since the start of the war have been expanding their road and rail infrastructure so they can move more by land in case ocean access is cut.

“By all reports, Ukraine can now move 50-60 per cent of its grain by rail or road, which is a huge advantage,” he says.

Rabobank grains market analyst Dennis Voznesenski.

When not analysing international grain markets for his employer, Voznesenski has been researching how different grains industries performed and managed the challenges caused by disruption from the first and second world wars last century.

“What I’ve found consistently is that the one thing that will stop the growth of a grains industry fastest is a poorly performing logistics system,” he said.

“Even if you can grow as much as you want, if you have no way of moving it to market, either export or domestic in an efficient way, then the producer loses money and has no incentive to continue or expand.

“I have contacts in Nigeria, where the logistics infrastructure there is about where Australia was in 1914. They don’t have rail infrastructure to move grain and they lose about 30-40 per cent of their harvested crop.

“Farmers there have no incentive to get better at what they do and why would they when they lose almost half of what they grow.”

While reluctant to predict a sudden collapse of Russia’s grains industry, Voznesenski says there are current factors and lessons from history that could spell real trouble for its people if the war continues.

“It’s already having a short-term impact, such as machinery that is increasingly difficult to maintain,” he said.

“Spare parts are harder to get and replacement machinery is near impossible to acquire.

“If you’re a Russian farmer looking to buy new machinery you can’t just order a John Deere header – they are now going elsewhere.”

Beyond the on-farm challenges, structural deficiencies generated by years of cronyism, corruption and waste also loom as major fault lines for an industry and economy under stress, Voznesenski says.

“When we think of farms here in Australia, we think about intergenerational operations, owned or managed by highly skilled professionals who’ve worked out how to make their farm economically viable without subsidies,” he said.

“In Russia, when the Soviet Union fell apart, they gave out state land to the mates of whoever held the power.

“Not only did they get the land they also got cheaper loans, cheaper fuel and cheaper electricity.

“So, faced with a costly war that’s going badly, and faced with sanctions and less income coming from overseas, what does the Russian treasury start to do?

“The most likely course of action will be to look for the fat in industries that have been heavily favoured and subsidised.

“If they target agriculture then many of those massive corporate farms will be unviable very quickly.

“And we all remember or have seen the images from the late 80s and early 90s, of people queuing in the streets of Moscow for food, when Russia was having to import grain because they had lost the capacity to feed themselves.”