Push comes to shove: Rural doctors dirty at being scrubbed from maternity wards

Rural doctors are warning they are being increasingly sidelined in the medical care of pregnant women as doctor shortages worsen and maternity units remain at risk.

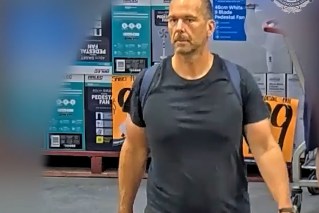

Rural doctors say they are being nudged away from involvement in maternity cases. Photo: ABC

The model that is being adopted to ease the workforce crisis is seeing midwives take the lead in maternity care, with doctors either excluded or their roles drastically diminished.

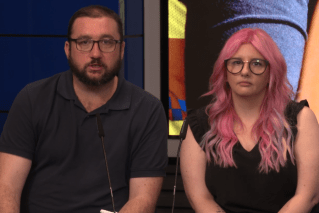

In some cases, doctors are no more than just “an authorising signature”, according to Rural Doctors Association of Queensland (RDAQ) president Dr Matt Masel, who says the move goes against the 2019 findings of the Palaszczuk Government-appointed rural maternity taskforce, which Queensland Health has denied.

He said the move was a further risk to women and their babies, particularly in rural communities that are more remote or where services have been downgraded.

“Exemplary maternity care is woman-centred and offers women a trustful relationship with their midwives and doctors,” he said.

“Doctors provide care through a relationship with their patients. If doctors’ involvement is reduced to an authorising signature, or as a requirement for funding, it is unsatisfying for doctors and increases risks for women.

“It can be distressing for a woman if their first introduction to their doctor is when their doctor is required for an invasive procedure or examination.

“It is also distressing for doctors to be first engaged at a point of crisis when they know this may have been prevented if they were involved earlier.”

The alarm from RDAQ comes amid an acute doctor shortage in the bush. The Rural Doctors Association of Australia (RDAA) has put the shortfall higher than 800 nationally based on unanswered advertised job vacancies.

Masel said the midwife-led solution was a quick, short-sighted fix that would further erode medical services over the longer term.

“At a service level it is a problem because it means well trained doctors are not being fully engaged to provide the range of skills they have been trained in,” he said.

“This impacts medical recruitment and retention and has consequences for the level of care available across a whole range of health care beyond maternity and birthing services.

“A key retention strategy for doctors is to create opportunities for them to have trusting clinical relationships with patients they care for and to be contributing to a trusted team.

“This creates a culture that supports everyone, most importantly, in this context, women and their families.”

The Goondiwindi GP said there was “resounding evidence” the best care models for rural maternity services were collaborative.

“They offer choice for women that provide parallel options, not one option at the exclusion of others,” he said.

“This is a keystone to rural health workforce and maximises choice and the mantle of safety for women, their babies and the whole community.”

As previously reported by InQueensland, Masel took his belief in the collaborative model as a solution to the current strains on clinical service to Health Minister Yvette D’Ath last month.

The idea is expected to get another airing next week when an urgently convened workforce forum on women’s health with a particular focus on support models for obstetricians and gynaecologists in rural and remote locations is held in Brisbane on March 2. Of the 39 maternity units operated by Queensland Health, 32 are located in rural centres.

A Queensland Health spokesperson said national workforce shortages in obstetrics and gynaecology – along with the maldistribution of those specialists – had made it extremely difficult to recruit and retain staff throughout Queensland, threatening the viability of maternity services in a number of regional and remote sites.

“We are exploring every possible solution to manage the delivery of neonatal, maternity, and gynaecological services in Queensland public hospitals where filling critical vacancies has been challenging,” they said.

“To ensure the health system remains safe and sustainable in the face of increasing demand and growing pressures, it is essential we have innovative models of care in place allowing for multidisciplinary teams to practice to their full scope.”

The spokesperson’s comments reflect recent remarks given to InQueensland by RDAA CEO Peta Rutherford, who said national issues affecting rural health would always hit harder in Queensland due to the higher number of rural towns and large regional centres spread across large distances.

But Masel remains convinced it is “entirely achievable” for small communities to resolve their workforce challenges with support, citing towns such as Longreach, Stanthorpe and Goondiwindi where “we know these patient-centred collaborative care models have thrived”.

He said the model was integral to the reopening of birthing services at Beaudesert in 2014 and Cooktown in the state’s far north a year later, the first and second maternity units in Australia to re-open after being closed in the wake of the medical indemnity crunch of the early 2000s.

Cooktown has been closed for birthing since the start of 2022, with pregnant women advised to leave their communities weeks ahead of their delivery date to birth in Cairns and sometimes Mareeba or as far as Atherton – more than three hours’ drive away – as back-up options.

Masel said full restoration of maternity services in Cooktown was unclear, with the resignations of two GP obstetricians over summer further eroding any hopes of re-opening.

“We know the acute loss of workforce and birthing services is very hard on the community and remaining staff,” he said.

“We are offering any assistance we can provide to the health service and Queensland Health to address local and state-wide workforce issues. “

Restoring the service and keeping rural health facilities viable and sustainable more broadly, he said, involved more than just the recruitment and retainment of doctors, underlining the challenge in front of health authorities in countless other Queensland communities.

“A key challenge in small birthing sites is maintaining critical staffing levels – not just of midwives and GP obstetricians, but also GP-anaesthetists, theatre staff and nursing staff who have trained in anaesthetic assistance,” Masel said.

“This whole team is needed to safely provide 24-7 birthing services, access to epidurals, and emergency caesarean sections when birthing so far from a larger hospital.

“This means women have access to the broadest possible range of choice and a mantle of safety through the birthing journey.”

Masel said birthing services were “like a keystone in rural health care”.

“When birthing closes, there is an additional challenge of how to keep the skills of the broader team current and how to keep recruiting to vacancies in those roles,” he said.

“Although staffing is a challenge, so is having a model of care and culture in which each member of the team is valued and trusted and this is the case for all rural birthing sites.

“Women deserve choice in determining their maternity team and who is best placed to provide their primary care. One of the choices is to keep her regular GP involved in her care.”