‘Our communities are sinking’: Will these Qlders be first Aussie climate refugees?

Rising sea levels are posing an imminent risk to the Australian shoreline, with tropical Queenslanders wondering when, not if, their islands will become uninhabitable, writes Aaron Bunch

Paul Kabai outside his Saibai Island home that is prone to flooding. (AAP Image/Aaron Bunch)

Beneath the roots of a weathered almond tree on a remote island in Australia’s north, traditional owners enrich the soil of their homeland with the blood and DNA of the next generation.

“This is the almond tree where my family bury our umbilical cords after a new baby is born,” Torres Strait Islander Paul Kabai says as he rubs its trunk and looks from his home to the sea. “It’s our traditional custom. I buried my children’s cords here but I don’t know if my grandchildren will be able to. The saltwater is killing my island, Sabai’s trees.”

Extreme weather and sea level rise are also destroying ancestral burial grounds and flooding streets despite a purpose-built seawall that is supposed to hold back the ocean. “The swell and tides crash over the top. I’ve had water come right under my house,” Wadhuam (maternal uncle) Kabai said.

The water also travels up the creeks that crisscross the island, swelling swamps and rising from culverts meant to drain the community.

It’s a similar story on nearby Boigu Island, where monsoonal swells have pounded the newly built seawall and flooded the community in recent months, according to traditional owner Pabai Pabai.

“It’s another sad reminder to us that our communities are sinking,” he said. “I worry what the Torres Strait Islands will be like for my grandchildren. How many will be left?”

The archipelago, which is located between Papua New Guinea and Cape York in Queensland, is on the frontline of the climate crisis, with sea levels rising six to seven centimetres in the past decade.

That’s double the global average, which is 3.25mm per year, according to The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Boigu and Saibai are flat, low-lying tropical islands about 1.5m above sea level, and like others in the chain of more than 200 islands, they are particularly exposed to sea level rise.

Climate scientist Dr Simon Bradshaw said most of the 17 inhabited islands’ communities are built on the coastline.

“There are certainly problems with rising sea levels eating away at land and homes and sacred sites,” he said.

“It’s naturally on those particularly low-lying islands, that include Boigu, Masig and Saibai, where the challenges are more acute.”

Experts warn that unless global CO2 emissions are curbed, sea levels will rise further and faster in the archipelago and could eventually overwhelm its communities, making them uninhabitable.

The seafaring Torres Strait Islanders could become Australia’s first climate refugees.

Weather is also predicted to become more extreme in the region, with more intense rain in the wet season, a longer, hotter dry season and more frequent and severe storms and cyclones.

Climate change and the warming ocean may also impact the region’s marine ecosystem, including coral reefs, turtles, dugongs and fish populations, which are traditional food sources for Torres Strait Islanders.

“There is nothing that drives home the urgency of the climate crisis more than what we are seeing in the Torres Strait,” Bradshaw, research director at the Climate Council, said.

“The communities there have done nothing to cause the climate crisis yet they are hit first and hardest by its impact.”

The damage, which includes saltwater contaminating fresh water supplies and vegetation loss, most often occurs from January to March during the monsoon season when waves and high tides inundate some islands.

During these months, monsoon winds strengthen and blow from the northwest over the Gulf of Carpentaria, pushing more water into the basin which piles up along the Queensland coast and in the Torres Strait, according to the Bureau of Meteorology.

Over the past three years, the highest sea levels have been in February, with 2023’s highest sea level measurement forecast for Monday.

Wadhuam Kabai said his community was worried the coming king tide would significantly breach the island’s seawall and cause more flooding and damage.

“In Saibai the seawater is already going over, and the Boigu seawall that was completed last year has already had water going over,” he said.

“We worry about our cemeteries, these areas have been damaged badly and gravesites have been removed.”

The cemetery, which is surrounded by a low wall to protect it from the sea, is littered with broken headstones that Wadhuam Kabai said were smashed by high tides.

The rising water is also damaging the mangrove forests that protect the shoreline.

Wadhuam Pabai said the ocean had already claimed hundreds of metres of his island.

“The January tide was only a little tide and what happened was it still went over the wall,” he said.

“This one will only be worse and cause more damage.”

Masig Island has also suffered significant erosion in the past year, with three metres of shoreline lost to the ocean in six months, according to traditional owners.

Climate change impact expert Donna Green said roads, schools, health centres, sewerage systems and other key infrastructure were being damaged on a regular basis.

“Culturally significant areas, including graveyards, have been destroyed, and areas that were reliable for growing staple foods have been inundated by salt water, devastating crops,” Assoc Prof Green of the UNSW’s Climate Change Research Centre said.

“The inundation is worst at the king tides early and in the middle of each year, but depending on the wind, the regular high tides are enough to breach sea walls and inundate areas, including flooding houses and buildings on a regular basis.”

Bradshaw said the damage would increase and become more frequent unless more is done to help Torres Strait Islanders adapt to the rising sea levels.

“We need to tackle the climate crisis and also get behind communities and their efforts so they can thrive and flourish and maintain their right to live where they are,” he said.

“They really have more at stake than perhaps anyone else because we’re talking about hundreds and thousands of generations of continuous habitation.”

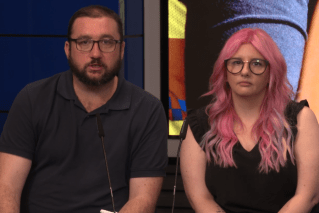

Wadhuam Pabai and Wadhuam Kabai, who represent their islands’ 13 clans, launched a class action against the federal government in 2021.

The men are arguing the Commonwealth has a legal responsibility to protect Torres Strait Islanders and ensure they are not negatively impacted by climate change.

The Federal Court is due to hear more evidence from the community in June and expert evidence in October.

“By failing to prevent climate change the Australian government has unlawfully breached this duty of care to us Islanders,” Wadhuam Kabai said.

They want the court to order the government to slash greenhouse gas emissions and save their islands from rising sea levels and other extreme weather impacts.

In September, the UN Human Rights Committee found the Australian government had violated its human rights obligations to Torres Strait Islanders by failing to act on climate change.

The Torres Strait, also known as Zenadh Kes, has a population of about 6500 people spread across about 500sq km of land and 44,000sq km of ocean.

This AAP article was made possible by support from the Meta Australian News Fund and The Walkley Foundation.