Our ‘field of dreams’: How two men created a city from a bush paddock and an idea

Ridiculed and dismissed when it was first mooted, the City of Springfield has quietened the doubters and pointed the way for cities of the future, writes Shane Rodgers

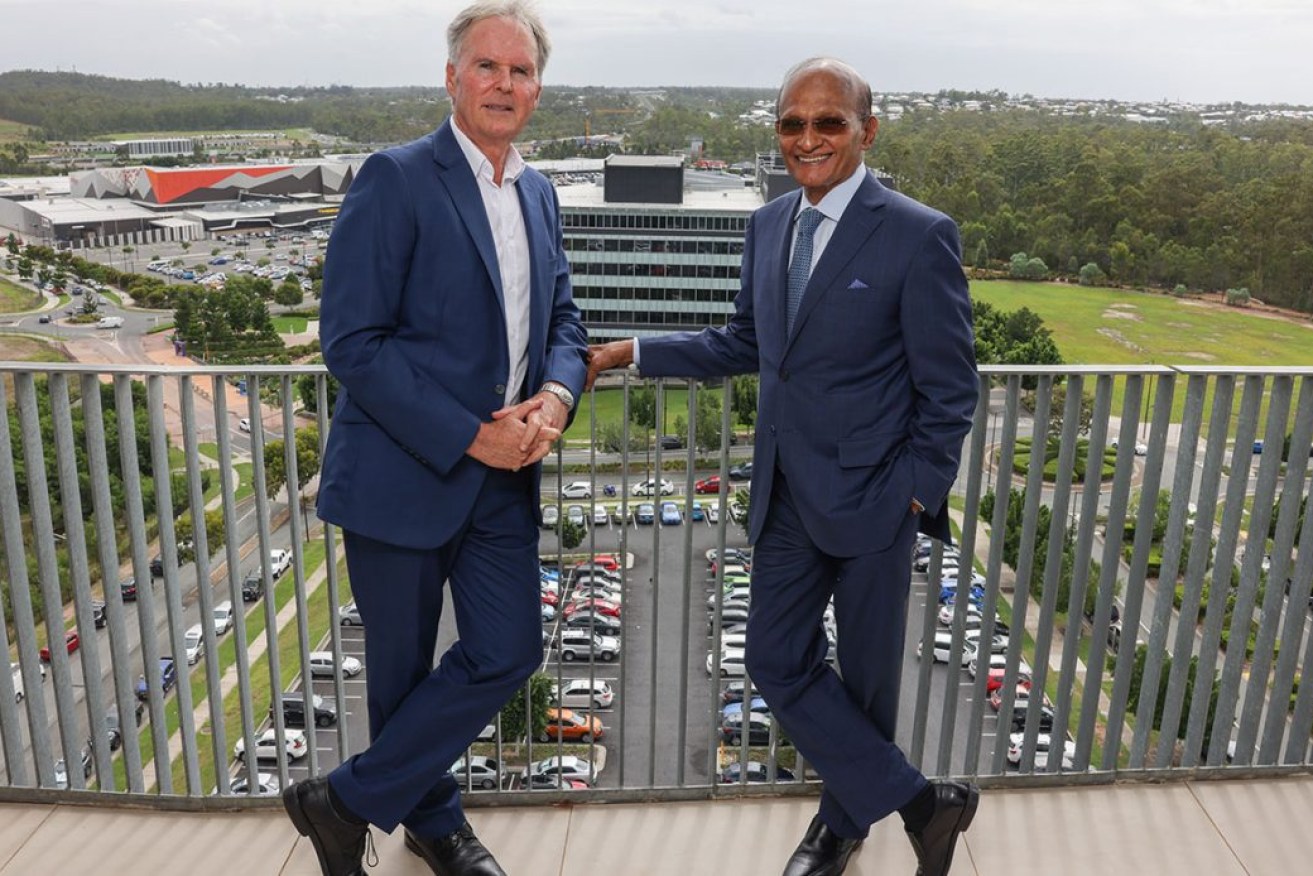

Springfield developers Bob Sharpless (left) and Maha Sinnathamby celebrate the 30th anniversary of the development. (Photo supplied).

Sometimes I imagine businessmen Maha Sinnathamby and Bob Sharpless staring out across a sprawling 2860-hectare paddock south-west of Brisbane, with a ghostly voice in their ears declaring “if you build it, they will come”.

Just like Iowa farmer Ray Kinsella (played by Kevin Costner) in the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, Maha and Bob needed faith, one heck of a vision and a force-field against scepticism. And Kinsella just had to build a baseball field for some ghosts. The founders of Greater Springfield were imagining a whole city.

That was 1992. Now, fast forward to 2022 where last night this curious urban creation known as Springfield celebrated its 30th birthday, with hundreds of friends and associates who formed part of the journey.

The paddock has long been consumed by development on a grand scale. The audacious vision that was Springfield now exists, a city of more than 50,000 people built on dreams, drive, tenacity and a little luck.

I think I was one of the first journalists to interview Maha Sinnathamby in the early 1990s. He was introduced by a friend and my interest was piqued by the tale of a grand city rising out of the south-western plains.

Back then, I was working for The Courier-Mail and had close to a 100 per cent success rate in having the stories I wrote printed. Sadly, the interview with Maha dragged down my batting average.

When the story about this bold venture did not make the cut, I went to the news editor to seek reasons why. The news editor was blunt. He said people would think we had “lost the plot” if we ran a story about a man that nobody had heard of claiming he was going to build a city in “clapped-out scrub country” at the back of Goodna.

Looking back. In 1992-93 terms, it was hard to question the assessment.

That was then.

Over the years I have kept in touch with Maha and Bob, visited the site and seen the bold PowerPoint vision presentations many times. I have attended events, become lost several times in the maze of suburban streets and realised that I have met many of the people who have streets named after them in the area.

As I was reflecting on the 30 years of Greater Springfield recently, it occurred to me that so much of the city of today still echoes those PowerPoint slides of the 1990s. There have been tweaks in strategy along the way, but the vision has been remarkably resilient.

What is more, the project provides a substantial case study on whether it is possible to build a city out of a paddock without a clear government, geographical or economic “big bang” to activate the core in a particular spot.

Of course, there are lots of planned cities around the world. Places like Washington, Brasilia and Canberra were purpose-designed through government impetus. However, these types of cities, particularly those drafted from scratch by private enterprise, are still well-and-truly in the minority compared with cities that grew organically from a geographical nucleus (ports, transport hubs, mineral finds etc).

While there will always be debate about whether Springfield is a real city, it has plenty of the trappings of what most of us regard as a city. It has population mass, a clear retail centre, commerce and jobs, medical and transport facilities, a deep education offering and significant “soft” community infrastructure.

A few newspapers have started there – a strong indicator of a free-standing community-of-interest in the area.

Springfield is seldom just written off as part of Ipswich (based on council boundaries) or part of Brisbane (due to proximity). It has earnt the right to have its own identity.

There are plenty of examples around the world where they built a field of dreams and people still did not come. In different circumstances, Springfield could easily have become just a collection of sprawling suburbs somewhere in the backblocks of anywhere.

In my view it avoided this fate because there was always a heart and soul at the core of the ecosystem. And the plan was always a stretch-vision, an insatiable, burgeoning dream intent on evolving into ever more advanced lifeforms.

Springfield was promising all houses would be linked to the World Wide Web before most people knew what the web was. It did not just have a golf course. It had a Greg Norman-designed golf course.

It always pitched in the A-league, capturing the imagination of national, state and local political and business leaders who could find no vaccination against the Springfield pandemic. Bob and the Sinnathambys seemed to be everywhere, using extraordinary networking skills to sprinkle Springfield credibility dust across the landscape and tattoo it into the psyche.

It managed to attract schools, a university, hospitals, big roads and rail lines seemingly at the speed of growth (or even ahead of it), in contrast to many areas of Australia that are always playing infrastructure catch-up.

With all that came a community mindset, and pride. Springfield City Group and its partners created the framework. The people did the rest.

Nobody ever apologised for living in Springfield. It had a bit of creative lustre. Outsiders did not necessarily know what was going on out there under a cloud of construction dust at the end of a convoy of tradies. But it had a certain “it” factor that set it apart.

Of course, it was not all triumph. There were lean years, setbacks and scepticism. It was always going to be hard to create jobs at the speed of population growth. Maha still struggles to get some people to set their scope wide enough to see the true scale of his city dream.

There was also some luck. Springfield was a “vision prepared earlier” when South-East Queensland was torched with an unprecedented population explosion in the 1990s. This new city on the Ipswich-Brisbane border became the jewel in the “western corridor” population strategy crown. Its existence became a convenient truth for policy makers attempting to corral the masses into an infrastructure-challenged region.

Of course, 30 years is not a long time in the life of a city built from scratch. The Springfield City Group aspires to create an internationally significant, innovative metropolis of more than 140,000 people.

These days few people would question the possibility. The Springfield story is only partly written. But it seems to be getting to the good part.

Shane Rodgers is a business executive, writer, strategist and marketer with a deep interest in what makes people tick and the drivers of change. Comments in this article are personal and not related to my day job.