Sharing the burden or just halving the profits – jury’s out on home buyer scheme

Brisbane economist Cameron Murray thinks politicians are too tentative when it comes to solving Australia’s affordable housing problem. He thinks we should look to Singapore for the answer, writes Robert MacDonald

House prices in Brisbane were tipped to rise again in 2024 (Photo: Hunter Galloway)

Is the Labor Party’s just-announced $329 million Help to Buy shared-equity scheme for home buyers a good idea?

Or is it just another case of a (would-be) government throwing money at a problem with the aim of being seen to be doing something?

Successive UK governments have supported, and periodically tweaked, a similar Help to Buy home ownership scheme since 2010.

It’s one of the models for Labor’s proposal, which aims to help 10,000 people into homes each year.

How has the UK program gone? That’s hard to tell exactly.

The House of Commons Library issued a research paper in December last year, which says, “Commentators have drawn attention to the lack of data on the outcomes of shared ownership schemes”.

It also notes such schemes haven’t been terribly popular.

Even after more than a decade of active government promotion, the concept is not widespread, with only about 200,000 – or less than one per cent – households living in shared ownership properties in England.

The House of Commons researchers identify complexity as a big problem. Hence the regular adjustments to the UK scheme, which range from deciding who’s eligible to rules about how home buyers can increase their equity share and sell their property.

Mortgage lenders have also been wary, seeing shared ownership as “complex and higher risk”.

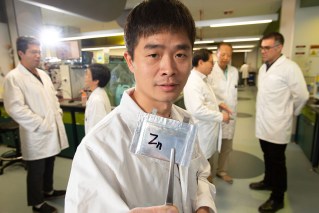

Brisbane-based economist Cameron Murray, with a PhD from Queensland University and a speciality in property and urban development, offers a similar take.

“Most schemes fail to attract substantial interest,” he says.

“This is because a home is both a place to live and an asset. Owners usually prefer to hold more of the housing asset value if they can get the leverage.”

In other words, most people buying a home typically are counting on making a tidy profit when they sell.

Sharing their eventual windfall with the government might seem a bit too much like a tax, even though that was the equity-sharing (and profit-sharing) deal they signed up for at the beginning of the mortgage all those years ago.

That’s means Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s immediate response to the Labor scheme – casting it as a revenue-raising strategy rather than an affordable housing program – might actually work as a scare campaign.

“What Labor have been very clear about is that they have a share in your home, and so as your home value increases, they are making money off you,” he said.

But if it is a revenue-raising scheme, it’s a long game given the multi-year length of most mortgages and the relatively low turnover of shared-ownership properties.

Murray also notes that because of mortgage-lender wariness of share-ownership schemes, private bank participation is limited.

“ Typically, the few banks that do participate, offer higher interest rates, undermining much of the benefits to residents.”

With that said, Murray isn’t against equity-sharing schemes.

“There are clear benefits to bringing forward home ownership for those who do participate,” he says.

But he asks why stop at the 30 or 40 per cent shared equity level proposed by the Labor model?

“Because if owning 30 per cent or 40 per cent of the equity in a home without charging any rent on that equity share is a good idea, then it is a good idea in general,” he says.

Murray has developed his own proposal of how to use government equity to help people into their own homes, which he calls HouseMate. https://fresheconomicthinking.substack.com/p/housemate?s=r .

It’s based on the Singapore model, where home ownership is close to 90 per cent and where 80 per cent of all dwellings in the past 50 years have been built by the country’s Housing Development Board.

Murray claims his proposal could halve the cost of buying a house in Australia but acknowledges there would be critics.

“Because HouseMate would divert first home buyers away from private markets, private sellers would find reasons to argue it would be bad for the people it helps and somehow financially reckless or unsustainable,” he says.

But he argues that because his plan involves using already-owned government land, the budget cost would be relatively low – peaking at $1.7 billion after seven years and falling to $640 million after 20 years.

“The $1 billion or so per year would provide 30,000 affordable houses per year,” he says.

Murray suggests the money could be found by taxing the gains private landowners receive through rezoning decisions, which he estimates at about $11 billion a year.

“Taxing those value gains could fund HouseMate 10 times over,” he says.

It’s a controversial suggestion, which would no doubt have its critics.

But perhaps the biggest problem with Murray’s HouseMates is that it’s a bold idea.

And this isn’t an election for bold ideas.

Instead, we’re being offered ideas such at Labor’s Help to Buy scheme, which recognises a problem but takes only tentative steps towards solving it.

But it does allow a future Labor Government to say proudly, “But look, we’re doing something, we’re spending $329 million”.